Victim or Enabler – also with the digitization it depends on the attitude

2. September 2018

SMEs and start-ups: the perfect combination for disruptive innovations?

9. November 2018W hen using robotic thinking, most people go directly to the destruction of workplaces and completely autonomous functioning systems. This skepticism is a good tradition in Germany; as early as 1978, the SPIEGEL magazine titled it with a robot and the striking credo “Progress Makes Unemployed“.

40 years later, we can state that this fear has not been confirmed in any way. With 42 million employees, more people are in work in Germany than ever before and that although industry, trade and even administrations have for many years been driving forward the digitization of their processes on a massive scale. A recent study by the WEF in 2018 even assumes that 75 million jobs worldwide will disappear through machine work by 2022, but no less than 133 million completely new jobs will be created. And this is only the beginning of a comprehensive transformation process (source: http://meschmasch.de/2018/09/19/fortschritt-macht-arbeitslos-nicht/).

New job profiles and replacement of skilled workers

Among these 133 million jobs will be job profiles that we don’t know exactly today. It takes a little thought experiment to imagine this for the future: One hundred years ago, 38% of the working population were employed in agriculture, their work was an essential part of the economic system and for feeding the population (source: https://www.bauernverband.de/12-jahrhundertvergleich).

If you had stood on a market place and told people that in a hundred years less than 1% of the working population would still be working in agriculture, you would have been confronted with a great lack of understanding. “What should we then feed ourselves on?” or “What should people do without their work?” would probably still have been the benevolent questions. If you had started to talk about millions of new jobs in “information technology” and about self-propelled harvesting machines controlled by satellites in space, people would have shaken their heads and turned away from them. In the same way, today we are discussing the loss of jobs due to the use of robots.

The conditions for an orderly transformation of our work and the use of robots in cooperation with people are ideal. Our demographic development ensures that over the next 10 years we will be sending a large number of skilled workers into retirement for whom there is no substitute in terms of numbers in the younger generations. This problem will not be solved by qualified immigration either, as this requires 250,000 immigrants per year.

Consequently, the only option we have is to use robots to increase the productivity of the human workforce if we are to maintain our level of prosperity. What is fundamentally changing is the nature of the activity and the cooperation between man and machine. In the future, industrial robots will no longer work in cages, but “hand in hand” with people. The latest sensor and safety technology makes this possible. Robots will also find their way into other areas, ranging from retail services to the household and even care or medicine. This raises fundamental questions about our understanding of the handling of robots, which we can look at using the example of care.

Machine support enables human care

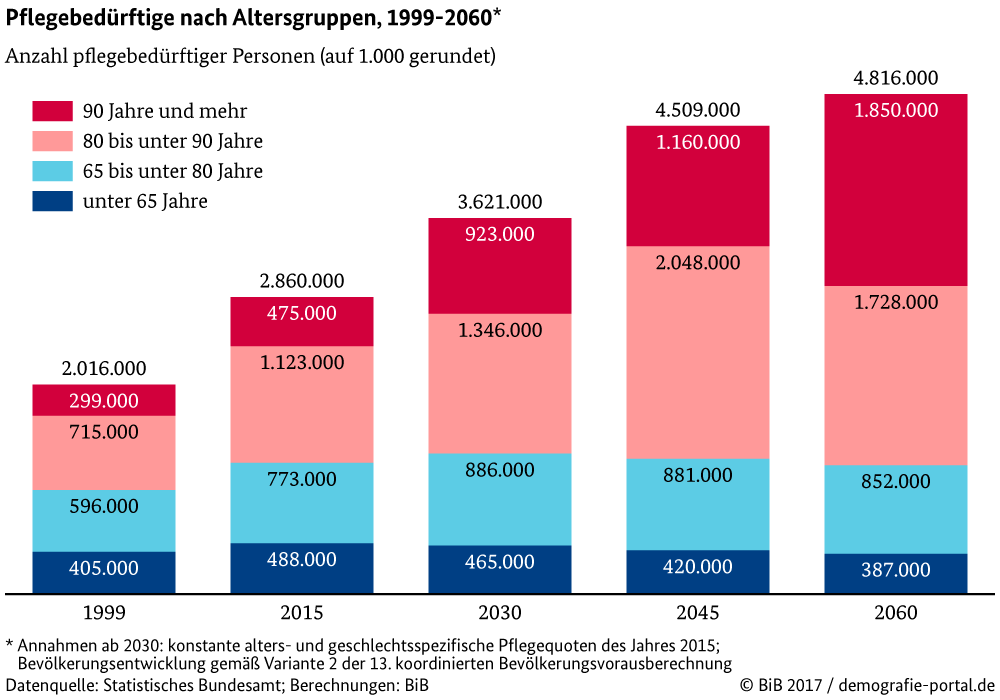

As the forecasts show, the number of people in need of long-term care is rising continuously and to such an extent that it seems almost impossible to cover the demand for long-term care workers via the labour market. We already have a shortage of nursing staff with almost 3 million nursing staff, which will become even more acute in the coming years. Despite this shortage, from an ethical point of view our demands on nursing care are enormously high; after all, the elderly should spend their old age in dignity and not be treated as “mass-produced goods”.

In addition to the necessary empathic abilities and the joy of helping old people, working as a carer also requires a good physical condition. After all, people need to be lifted out of bed and similarly strenuous activities. Here, as in industry, the use of mechanical support would be worthwhile in order to minimize typical clinical pictures such as back pain or joint wear and tear and thus enable the nursing staff to do a good job until retirement.

Even the thought of a robot being used in nursing care meets with rejection in Germany from many, after all it is “inhuman” to imagine that one is lifted around by a robot. In my opinion the discussion is led from the wrong perspective. If one looks at the conditions for the nursing staff, one can assume here in the current system – without a nursing robot – that the conditions are sometimes inhumane. In fact, there is no time left for personal interaction with those in need of care, as the number of caregivers is constantly increasing. In the end, there is just enough time to carry out the most necessary and not necessarily most pleasant activities. That this can be not only physically, but also psychologically stressful is out of question.

Let’s imagine the team consisting of a care robot and a human caregiver who do the tasks hand in hand. For the caregiver there is some time to communicate with the patients, while the robot takes care of the most necessary tasks. The robot thus allows more time for interpersonal activities and noticeably relieves the caregiver physically in her job. In the end, we not only achieve higher productivity (assisted care cases per caregiver), but also that the caregivers can concentrate on the interpersonal relationship and thus improve the quality of care.

Conclusion – machines can do everything that can be standardized

Let us therefore move away from a narrow view of robotics and make it possible to define human-machine cooperation in a positive way. In the end, a robot can take over all activities that can be standardized and are often annoying for us in their execution. The human being uses his core competence in this system in order to create greater added value with creativity and emotional intelligence!