Towards a digital society – what businesses should take into account in cultural change

3. June 2019

Digitization in medium-sized companies – but secure!

9. August 2019T

he use of algorithms is an essential building block in the digitization of companies. These are computer programs that search for certain patterns in data or, for example, provide results for search queries via if-then links. One of the most famous algorithms is Google’s search algorithm, a program that is now more than 2 billion lines of code long and serves only one purpose: to provide better and better search results for queries on the Internet.

In the vision of many digital thought leaders, algorithms are taking on more and more decisions, enabling a highly automated and increasingly efficient system. Especially in an industrial context, when it comes to the control of complex systems, algorithms in an industry 4.0 environment are already taking on important tasks in condition monitoring and may already decide what to do if errors are detected in the system. Algorithms are also increasingly being used in management. For example, in large companies, incoming applications are pre-sorted by algorithms.

The discussion about autonomous driving shows that we very quickly reach ethical limits when making decisions using algorithms. A central question of acceptance there is how the vehicle – i.e. the algorithm installed in it – should decide who should steer the vehicle, a child or a senior citizen, in the event of an unavoidable collision.

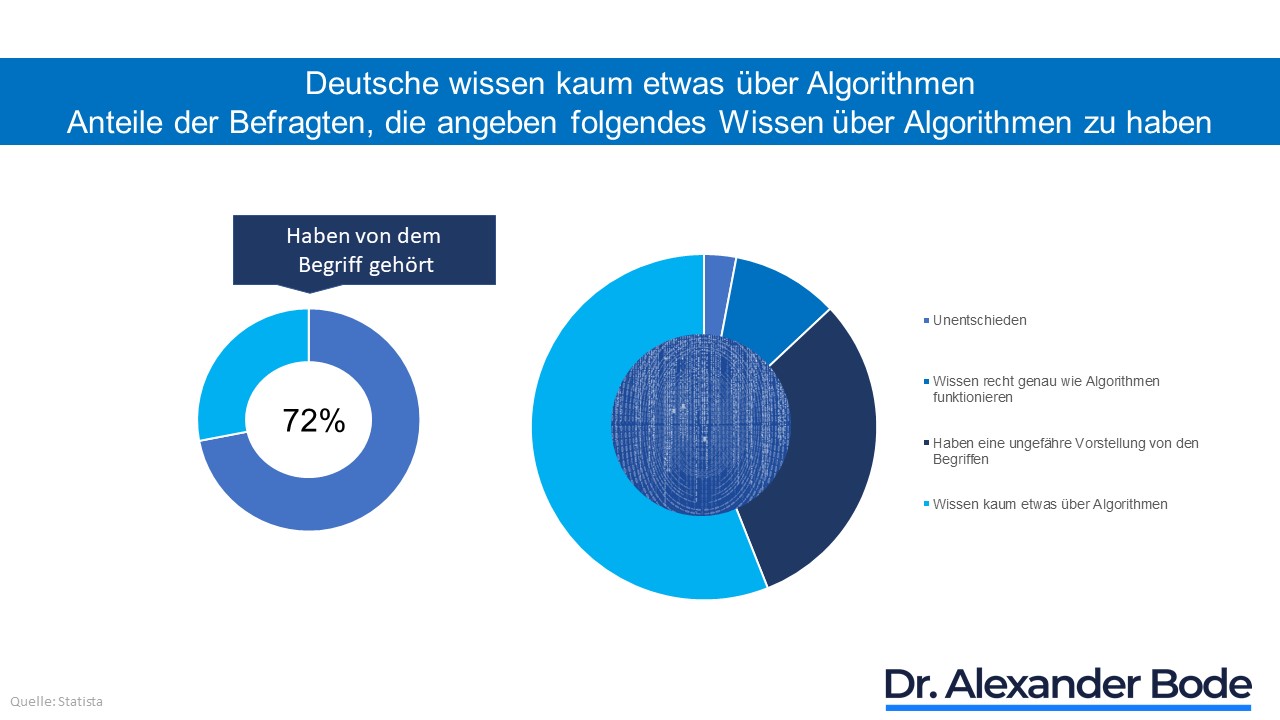

In my opinion, this discussion, which can easily be transferred to the entrepreneurial context, shows two things clearly: firstly, we have a great deal of confidence in the performance of these algorithms and secondly, we still have far too little comprehensive understanding of the nature and functioning of algorithms. The first is a question of technology, combined with the consideration of whether it will ever be technically possible to develop systems so fast that they can make such complex decisions within milliseconds and then initiate all the necessary measures. The second, on the other hand, is a deeper social problem: we are increasingly placing ourselves in the hands of algorithms, both professionally and privately, without knowing exactly what they actually are, as the statistics impressively show.

It is therefore particularly worthwhile for companies, before making a decision on the use of algorithms, to look more closely at the question of which decisions could actually be made technically by algorithms in the future and which should be made entrepreneurially.

What is an algorithm?

Generally speaking, an algorithm is a way of solving a problem. Using this solution plan, data from one or more sources is converted into output data in single steps. While algorithms play an important role especially in computer science and mathematics, they can also be formulated and processed by humans in natural language. In principle, the algorithm carries out three steps: the acquisition of data (= information), the processing and finally the output of the processed information to an actor.

As the amount of data increases, the processing by powerful computers is very efficient, provided that an algorithm has the following properties, among others:

- Uniqueness and determinacy: an algorithm must not have any contradictory description and must always deliver the same result under the same conditions (at most one possibility of continuation).

- Executability and finiteness: every single step must be executable and the algorithm must deliver a result after a finite number of steps.

In addition to these properties, the use of “artificial intelligence” leads to the fact that an algorithm can be able, for example in machine learning, to take into account the experiences with its results in the future. In this case, the algorithm is no longer completely programmed, but “trained” in its own learning system and is thus able to develop independently.

This ability to change raises the question of what role a learning algorithm can and should play in a company in the future.

Who takes responsibility for algorithmic decisions?

Algorithms are already ubiquitous in companies today and can provide enormous support, especially in the processing of administrative processes. But it is questionable whether algorithms can and should make far-reaching decisions for companies in the future? Technologically, it will be possible in just a few years to let algorithms make complex management decisions. However, there is the problem of responsibility and liability.

Let’s take a fictitious example: Volkswagen is currently suing some (former) managers for their decision on the shutdown devices and exhaust gas manipulations. They are to bear the responsibility for the fact that things were done as a result of which the Group had to pay many billions of EURO in fines and compensation. Imagine who would be in the dock if an algorithmic decision had been made. The developer of the software? The buyer who decided to buy the software? The legal advisor who did not stop legal decisions?

On the other hand, one could of course argue that in our fictitious example, the algorithm would never have supported such an “illegal action” and thus the damage would not have occurred at all. So is the algorithm the better decision maker because it ignores other factors, such as career pressure or social pressure? However, such a decision would have had completely different consequences, for example a decline in turnover in this submarket, and possibly even job losses. And who would have taken responsibility for this?

So let’s keep in mind that at the end of the day the algorithm can never take responsibility for decisions, but only the people who use it. This applies above all to entrepreneurial decisions, which are always made in a situation of uncertainty. They are therefore not deterministic, i.e. precisely predictable. This has to do with the fact that people’s behaviour is not one hundred percent predictable. However, since corporate actors (i.e. legal entities), unlike natural persons, must always represent their decisions vis-à-vis third parties, they are subject to a special duty of care.

Deutsche Bank, for example, can only make and represent its entrepreneurial decision to radically restructure on the basis of the information available to it, but does not know how the market, customers, the public and employees will react to this overall. Such fundamental decisions are neither deterministic nor can they be repeated at will, so that learning or training processes could be set in motion here.

Standardizable decisions – YES!

In summary, AI-based algorithms can make many “decisions” that are based on standardized procedures or take place within very clear regulations. It is important that the incoming information is of comparable quality so that the basis for the decision is comprehensible. It is also important that in self-learning systems it can always be understood why decision patterns may change. If these prerequisites are met, algorithms can efficiently support the work of the employees in the company.

For companies, this means getting algorithms into the processes where standardized decision paths are involved. Conversely, you give your employees more time at all other points to familiarize themselves with the complexity of the facts and to make qualitatively good decisions with corresponding recommendations of algorithms.

Where do you start tomorrow?

As mentioned at the beginning, there is still a great deal of ignorance and uncertainty, especially with regard to algorithms and artificial intelligence. Before they force the use of algorithms for decision support, they should therefore educate their staff as to what lies behind a new software or algorithm and, above all, what benefits it can bring to employees:

- Together with your employees, analyze where in the process support through algorithms can improve work quality or reduce workload.

- Involve your employees closely in the design of new processes so that they understand the benefits for their own work from the start.

- Provide training opportunities for all employees whose work is (partially) eliminated by the introduction of software.

- Establish clear rules that make it clear who makes the decisions in the company (“the person and not the algorithm”).

Even if the algorithm is not the “panacea” and will not take over the complete management of the company, an application in more and more processes in the company is indispensable in order to remain competitive. Take advantage of this opportunity.

#einfachmachen

Quellen:

https://www.datenschutzbeauftragter-info.de/was-ist-ein-algorithmus-definition-und-beispiele/